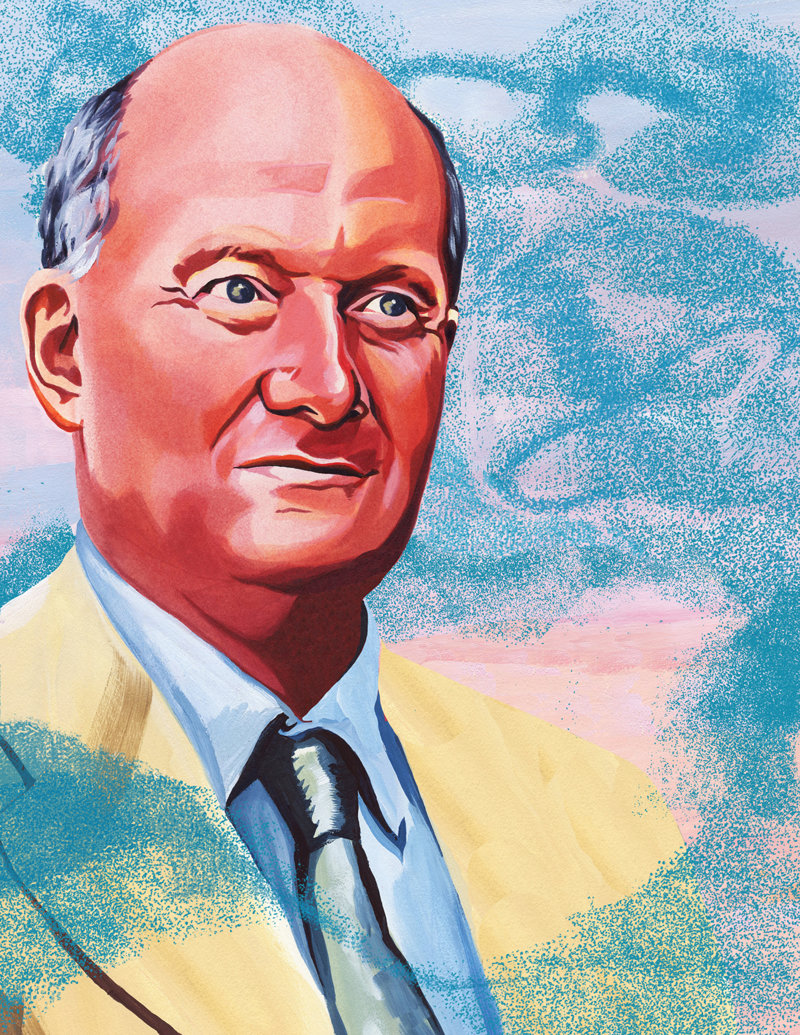

Jennifer Lankheim talks with sociologist Massimo Introvigne, founder and managing director of the Turin, Italy-based Center for the Study of New Religions, about the intersection of art, freedom of belief and religion.

One of the world’s leading authorities on religion and its societal impact, in 2012 Introvigne was named by Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs as chair of that nation’s Observatory on Religious Liberty. The conversation took place in Los Angeles, at the Church of Scientology Celebrity Centre International.

Can you give me a brief overview of your work as it relates to the Church of Scientology?

Massimo Introvigne: I’ve been researching new religious movements for the last 35 years. In the context of modern religions, the Church of Scientology is one of the most important. I’ve followed the activities of the Church for 25 or 30 years, and I helped publish a 100-page book on the Church by the American scholar Gordon Melton [The Church of Scientology (Studies in Contemporary Religions, series volume 1), Signature Books, 2000]. I was the general editor. I have also participated in conferences about Scientology; the last was one year ago in Antwerp, Belgium.

Currently I am researching the religions that are impacting the lives of professional artists. That’s my reason for being here [in Los Angeles], to interview artists who are parishioners of the Church.

Tell me more about that project on the intersection of religion and art. What piqued your interest in that subject?

There is something about modern art we very often see, even in college and high school textbooks, that I believe is not entirely correct. They say that traditional art up to the Enlightenment was religious art—Christian in the West—and that modern or post-modern art has been completely outside the religious field—that it’s materialist, Marxist. And that’s not the case. There are some important modern artists who are active Catholics or Protestants or Jews, and the newer religions have had a surprisingly crucial impact on very beautiful modern art.

My work in this area started with the Theosophical Society, whose artists like Wassily Kandinsky or Piet Mondrian had a great impact on abstract art. It took time, but a significant number of scholars now acknowledge the impact of theosophical ideas on modern art.

Then I realized that other religions, comparatively recent, also had an impact. And having studied the Church of Scientology, I started wondering whether it too had an impact on the art community. And I found out that, as a matter of fact, the Church actively promotes the arts. Among the founders of modern religions, L. Ron Hubbard was one of the more interested in the arts. He wrote extensively on the subject.

I think we are seeing increasing evidence that in its vast majority, modern art is not against religion. Modern art has much less connection to traditional, institutional religions—Catholicism, Protestantism, Judaism—than classical art. But it has connection with newer forms of religion and spirituality, including Scientology.

So there’s a whole field of study. I’m preparing an issue of a magazine published by the University of California Press called Nova Religio, concerning new religions and the arts. I am also preparing, hopefully, a book.

What are you finding about the connection between modern art and religion, as compared to the relationship between religion and classical art?

The relationship is different. In the Middle Ages, almost all art was religious and the role of religion was patron. The religion commissioned the artist to paint for the church or for the palace of the bishop or for the religious monument in the square.

We cannot take a knife and fragment religious liberty. Either we defend the religious liberty of everybody or we don’t defend it at all.

Today, the role of newer religions is not the role of patron. Yes, there are a few walls and murals done in the centers of churches around the world. But that’s not the important part. It’s much more the role of proposing aesthetics and ideas about art that may serve as an inspiration. The example with Scientology would be Mr. Hubbard writing books or giving lectures about the arts, and slowly these ideas get into the artistic community through artists who are Scientologists.

It could be said conversely that art defines religion in some ways, in that it influences perceptions. For example, classical artists shaped how we imagine—and even worship—Catholic idols. Is modern art working in that way to ‘brand’ religions like Scientology?

I think it is and it isn’t. For instance, one of the artists active in the Church of Scientology, Pablo Roehrig, did a painting actually representing the Church’s concept of the Bridge to Total Freedom.

But mostly I think artists, in the Scientology example, do their own art inspired by Mr. Hubbard’s ideas of what art is, what aesthetics is. Also, I think having your own artistic community within a religion is a sign that it is evolving towards the mainstream, in that ‘mainstreaming’ is a process.

In the 30 years you’ve been studying religions, the world has changed a lot. How has your work changed with the times?

We are doing this issue of Nova Religio on new religious movements and the visual arts. We would never have done this in the 1990s, when there was so much controversy. Now we can talk about new religious movements and the arts, new religious movements and globalization, new religious movements and theology.

Of course, controversy will always be there. Controversies are still there about Islam or Catholicism after thousands of years. But I think it reflects the maturity of this field of study that it does not define itself only in terms of the controversies. Normally, in their infancy, new fields in sociology or history are defined by controversies. When you grow up, you don’t ignore the existence of the controversies. They’re still there. But you don’t deal with them exclusively or primarily—you explore the other dimensions.

Religious freedom is another area in which you’ve taken a special interest in your career. Tell me about your work in that area.

I took a sabbatical in 2011 and served as a representative for combating religious discrimination with the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

OSCE’s 57 member states include the United States and Canada. I was very surprised because, given my background, I expected to receive many files on my desk about discrimination against new religious movements. In fact, I only received one or two. Most instances of discrimination were against traditional religions.

A central problem is how you define religious freedom versus other freedoms. I’ll give a dramatic example: Charlie Hebdo, where radical Islamic fundamentalists killed cartoonists. About two years before that incident, I attended a conference on Islamophobia. Many Muslims came to say that their religious liberty was threatened by Charlie Hebdo and similar publications because they were not free to walk in the street without being offended by posters attacking their religion. So, who is right here? Because, of course, we all agree it’s wrong to go with a gun and kill the cartoonist.

Today in the area of religious freedom, we have large problems. There are massive violations of religious freedom, with people actually killed by ISIS, Boko Haram and other terrorist organizations. How do we react to this? Are we capable of reacting? Or do we just stand and watch in horror as Christians and also Muslims of a different persuasion are beheaded on YouTube? What do we do? We can always call a meeting of the Security Council at the United Nations and say, “We condemn in the strongest possible terms….”But people keep getting killed every week. That’s the problem of the biggest magnitude.

I think all these things are connected. We cannot take a knife and fragment religious liberty. If we don’t defend the religious liberty of all groups, we’re not credible when we say we want religious liberty for Yazidis in the part of Iraq controlled by ISIS, or for Christians in Pakistan, or for evangelical churches when they refuse gay marriages. Either we defend the religious liberty of everybody or we don’t defend it at all.

These problems with respecting the beliefs or the non-beliefs of others is maybe the only thing that is as old and consistent as religion itself. From your vantage as someone immersed in these issues for 30 years, what is at the heart of all this tension?

It’s an interesting problem, because it’s a common misconception that most religions persecute each other. This is not entirely false, but to say this is the whole of the problem is false. We saw the wars of religion: Christians against Muslims, Muslims against Christians, Catholics against Protestants, Protestants against Catholics, everybody against the Jews. That’s as old as humanity and religion itself.

But I would say that particularly after the horrors of World War II—the Holocaust—and also the killing of the Armenians [during and after World War I] religions for the large part have been trying to clean up their own act. There’s now a consensus among the most respected authorities in Christianity, Judaism, and increasingly even in Islam, that people who kill or persecute in the name of religion are wrong.

Now, of course, in Islam they have to struggle with the fact that they’re not a vertical organization with somebody like the Pope or a president of a church deciding things. But I would say that even in Islam they have made much progress after 9/11 in the line of dialogue, and the most respected authorities in the Islamic world would not condone terrorism.

Today, if we see ISIS hitting Christians and Yazidis and Shiites, it’s not a small problem, but it’s a geographically localized problem. You don’t see Muslims beheading Christians or Christians hanging Muslims in the United States, or in Europe or Latin America. It’s still a big problem—religions persecuting one another in these heinous ways—but it’s localized.

Now, there’s a second phenomenon we should not overlook, and this is of secular ideologies trying to marginalize religion. And that started with the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, perhaps as a reaction to the excessive power of religion in the years before the French Revolution.

Scholars agree that the French Revolution was very different from the American Revolution. Both separated church and state, but as one of my French colleagues likes to say, France separated church and state to protect the state from the church, and the U.S. separated church and state to protect the churches from the state.

Basically the French Revolution launched aggressive secularism. In Europe particularly, secularists severely reduced the influence of traditional religion. Lo and behold, all of a sudden new religions came. The secularists were not expecting that. And so they became quite angry and started studying strategies to make sure these new religions didn’t replace the old ones and didn’t carve a niche too big for themselves. But in the end they didn’t succeed, because one of the problems of secular ideologies is they don’t persuade the majority of the population.

The majority of the population still craves religious and spiritual fulfillment, and answers. Who am I? What’s my destiny? For what purpose am I on this planet? And no matter how strongly secularism promotes its own agenda, it will remain an ideology for a minority.

And looking to the future?

Religion will change, but it will remain an influential factor for centuries to come. Perhaps the practice of going to church on Sunday will be replaced with another form of being religious or spiritual, even in Christianity. But religion is here to stay. Every time religion has a revival of some sort, secularists become angry and start screaming. But they should probably learn to live with the fact that religion is not going to disappear anytime soon, and perhaps never.

It will metamorphose. That it has done throughout history. But religiosity or spirituality, we have evidence enough historically and sociologically, it’s something human beings want—to have answers. Science supplies some answers, of course. But it’s not enough. Religion is here to stay.