“The safety of our patients is our highest priority and we take the delivery of safe care extremely seriously.” —Hospital manager for Cygnet Kenney House

From Langdon Hospital in Dawlish to St. Andrew’s Healthcare in Northampton; from Cygnet Kenney House in Oldham to Edenfield Centre in Greater Manchester; from the assessment center in Maidstone to St. Martin’s Hospital in Canterbury—no corner of Britain is immune.

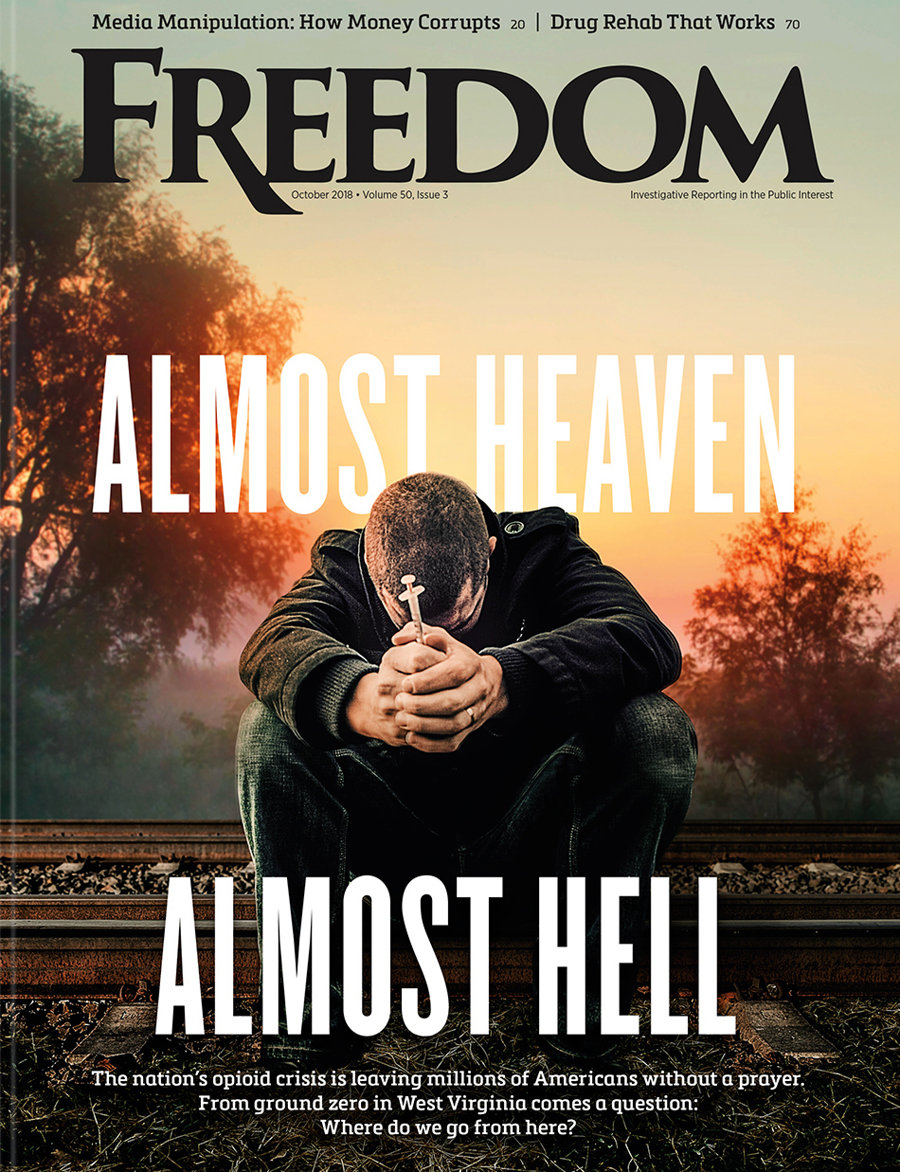

Institutional psychiatry in the UK is an egregious assault on human rights, riddled with emotional, physical and sexual abuse.

Report after investigative report adds to the pile.

CCTV footage captured a staff member grinning for the camera as the atrocity unfolded.

Citing poor safety standards, out-of-date and mismanaged drugs, staff shortages and delayed responses to critical incidents, the UK Care Quality Commission (CQC) issued a serious warning to Cygnet Kenney House, a private mental health unit in Oldham, after inspectors uncovered widespread failures that left vulnerable patients unsafe.

Inside a “high-dependency” rehabilitation unit for women with complex needs, patients reported feeling frightened and ignored. Staff were described as too busy to respond to distress, with one patient told to “stop crying, you are making me sad.” In two other wards, inspectors found failures to properly monitor food and fluid intake, while patients were kept under observation longer than clinically recommended.

The findings come amid escalating scrutiny of private psychiatric providers nationwide, with none more emblematic than St. Andrew’s Healthcare in Northampton. A December 12 inspection report detailed allegations involving around 600 patients, exposing a hospital culture stripped of care, scornful of accountability and reveling in abuse.

In one documented instance, a patient was kicked, had their airway restricted and was struck in the face while 17 staff members stood by. None reported the assault. CCTV footage captured a staff member grinning for the camera as the atrocity unfolded.

Footage captured at least 26 additional violent incidents. In one, staff were seen leaning on a patient’s joints and forcing them forward by applying pressure to their back. In another, staff dragged a patient into seclusion with their genitals exposed.

Patients were restrained using dangerous techniques, including being pinned down by their chests—on one occasion for 75 minutes.

The incidents led to a police arrest and condemnation from MP Mike Reader who was “horrified” to learn of the violence and abuse committed in the name of help.

Words like “humiliated,” “bullied,” “improper,” “abusive,” “inappropriate” and “unsafe” pepper these reports.

All of the investigations, undercover exposés and public cries of outrage—far too numerous to catalog in one article—occurred in the past year alone.

And none of this is new.

Institutional psychiatry in the UK was proven fatal long ago. In June 2025, ward manager Benjamin Aninakwa was convicted over the 2015 death of 22-year-old mental health advocate Alice Figueiredo, after staff repeatedly ignored her self-harm attempts. The psychiatric conglomerate Priory Group was fined £650,000 over the 2020 death of 23-year-old Matthew Caseby, who escaped from a Priory psychiatric hospital in Birmingham and later died after being hit by a train.

Yet despite abuse and death, the UK’s private mental health clinic providers continue to enjoy a cushy relationship with the National Health Service. As reported by Freedom, the NHS pays these private, for-profit providers nearly £800 (over $1,000) per patient per day—roughly £300,000 (nearly $400,000) per year for a single bed.

In total, the NHS spent more than £2 billion in 2023 outsourcing psychiatric care to private hospitals. That’s over $2.5 billion spent on suffering and suicide.

Defending this arrangement last year, UK Health Secretary Wes Streeting said, “The independent healthcare sector … can help us out of the hole we’re in. We would be mad not to.”

The Centre for Health and the Public Interest (CHPI), an independent think tank monitoring the NHS, called Streeting’s statement “utter nonsense.”

And in the understatement of the millennium, one spokesperson confronted with the festering wound passing for his hospital said, “We acknowledge that care at our Northampton hospital hasn’t always met the standards every patient deserves, and we are sorry to those affected.”

Such limp statements follow a dog-eared script—and are delivered after the footage is reviewed, the inquiries conclude, the fines are paid and the patients are buried.

What remains unchanged is the system itself: one that confines the vulnerable, shields abusers and puts public money into bloodied hands.

In Britain’s psychiatric institutions, human suffering is not a failure of the system—it is the business model, subsidized by the state.